Notes

Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) dedicated Il Cimento dell’ armonia e dell’ invenzione, the publication that starts with The Four Seasons, to the Czech count Wenzel of Morzin, or as he was known locally, hrabě Václav z Morzinu. In the dedication, he lists Morzin’s various Bohemian and Habsburg honorifics, “Lord Václav Count of Morzin, hereditary lord of Vrchlabí, Lomnice, Čistá, Křinec, Kounice, Doubek, and Sovolusky, current Chamberlain and Counselor to his Majesty the Catholic Emperor.”

A simplified Czech pronunciation guide follows this essay.

Bohemia

What is Bohemia and who are the Bohemians?

Boiohæmum is the name that Imperial Romans used in the first century B.C.E. for the region settled by the Celtic Boii tribe, located roughly within the same geology that defines the modern Czech Republic. The word became Bohemia in later Latin. Migrating Slavic tribes that called that same region “Czechy” began replacing the Boii around the 6th century C.E. Today, Czech and other modern western Slavic languages call the region by the name Czechy or something close to it, such as in Slovak, Polish, Silesian, Estonian, Slovenian, Upper and Lower Sorbian, Serbian, Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, and Chechen. while most other European languages, including Eastern Slavic, favor the Latin-derived name, such as Bogyemiya in Russian(), Ukranian, Bulgarian, and Belarusian.

The larger Czech territory included the historical countries Bohemia (Čechy), Moravia (Morava in Czech), and Czech Silesia (České Slezsko in Czech). The baroque composers on this program—except Vivaldi—came from these regions of Bohemia.

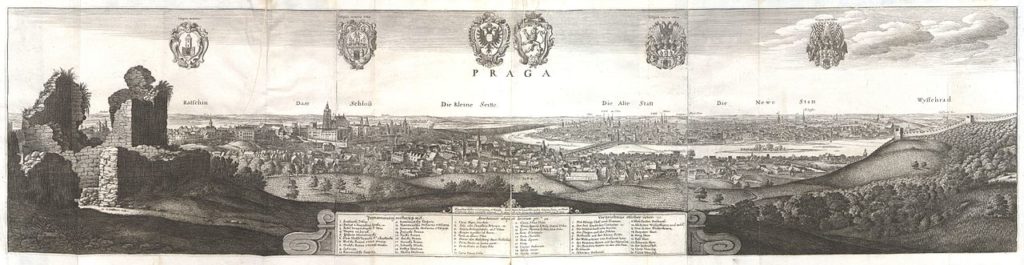

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677), Panorama of Prague in 1636 (digitally retouched). Wikimedia Commons.

Ethnic Germans had existed alongside the ethnic Slavs in Bohemia since medieval times. In 1609, Emperor Rudolph II made Prague capital of the Holy Roman Empire. But in 1620, in an act of the Thirty Years’ War, the city lost its capital status, and its cultural standing declined. Its Austrian rulers and Habsburg nobility looked outwards to Vienna, relegating Bohemia to a backwater.

With a few exceptions, work for musicians within Bohemian lands dried up, forcing local talent to look farther afield to practice their craft. As German had been an official second language of Bohemia since 1627, Germany and Austria became natural destinations for a new class of economic migrants: musicians.

The Music

We complete our tour of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons with “Summer,” the second violin concerto in his Cimento dell’ armonia e dell’ invenzione (trial of music and rhetoric). The titles both of the collection and of the concerto are bound to the idea of telling stories through music wordlessly.

Vivaldi constructed the three movements of “Summer” around a sonnet that describes a changing summer scene. Unlike the other three seasons’ sonnets, which present tableaux with incidental humans, like a Canaletto painting, “Summer” follows a single character, a shepherd, through the landscape. The left column of the translation below shows about how long into the movement the depicted passage starts in the music.

In a stroke of genius, Vivaldi crafted the first movement of “Summer” as a musical chimera—a single organism with the genetic material of two—here manifested by two ritornello themes when there would normally be just one. The first ritornello, marked “not very fast,” shuffles along downbeat-less, conjuring a wilting heat. Birds and gentle puffs of breeze briefly break the oppressive swelter until strong gusts from the north, marked by the second ritornello, announce an imminent, menacing summer storm.

The middle movement illustrates the shepherd’s anxiety as the storm draws closer, and the concerto closes with another ritornello-based fast movement depicting the storm in full fury. Rather than complete the ritornello’s phrases in the normally expected way, Vivaldi interrupts it repeatedly to underscore the disruptive violence of his storm.

Illustrative Sonnet on the Concerto Titled “Summer”

| 1. Sotto dura staggion dal sole accesa Langue l’ huom, langue ‘l gregge, ed arde il pino; Scioglie il cucco la voce, e tosto intesa Canta la tortorella e ‘l gardelino. Zeffiro dolce spira, mà contesa 2. Toglie alle membra lasse il suo riposo 3. Ah, che pur troppo i suo timor son veri |

In the harsh, sunburnt season man and beast wane, pines dry out; a cuckoo’s unrestrained voice is soon heard, a turtle dove sings, along with a goldfinch. Zephyrus2 blows gently; then a challenge: Fear deprives his weary limbs of rest Ah, how his fear was all too justified |

__________

1 borasca: a squall, derived from “Boreas” (see note 3)

2 Zephyr: west wind (Greek ζέϕυρος); a gentle breeze

3 Boreas: north wind and its deity (Greek βορέας); a blustery, blasting wind

__________

Capricornus. Wikimedia Commons.

Samuel Bedřich Capricornus (1628–1665), also known as Samuel Frederick Bockshorn, came from Zerčiče near Mladá Bolesov, about 31 miles northeast of Prague. His family took refuge in Hungary when he was still a boy, fleeing religious persecution. Centering his musical career in Vienna and Stuttgart, he became a prolific composer with over 400 pieces in his catalogue, though many of them are lost or fragmentary. His work enjoyed wide circulation, and his church compositions stayed in use into the 18th century.

Today’s Sonata for 8 Instruments comes from a set of manuscript partbooks held in the Uppsala University Library in Sweden. This early baroque piece pays tribute to the innovations of Venetian composers of Monteverdi’s era. It features a triple-choir texture: 1) a pair of soloistic recorders, 2) a pair of equally soloistic violas, and both pairs set against 3) a four-voiced instrumental choir. When the entire ensemble plays together, the upper eight parts share equal melodic importance, an ideal of late Renaissance music.

Johann Gottlieb Janitsch (1708–1763) came from Świdnica (Polish: shfid-NI-tsa), part of Polish Silesia but a mere 13 miles from the Czech border. Janitsch’s talent caught the attention of the future Frederick the Great while Janitsch was still a law student at the university in Frankfurt an der Oder. Then-Prince Frederick hired him for his permanent musical retinue. When, as king of Prussia, Frederick diverted arts funding to his military expeditions, Janitsch presented private musical soirées in Berlin to support himself.

With a flair unique to Janitsch, the Quartet in D minor merges such current aesthetics as the melodic contours of an emerging classical style, the kaleidoscopic counterpoint of the German high baroque, and Enlightenment-influenced structure. It comes from a Berlin archive that the Red Army took to Russia at the end of World War II. This quartet and other Janitsch works, unknown until the archive’s 2001 repatriation and transcribed from manuscripts in Berlin by Tempesta’s directors, will comprise our next CD.

Bohumír Finger (1655–1730), who went by the names Gottfried in Germany and Godfrey in England—all meaning “God’s peace”—came from Olomouc, the historical capitol of Moravia. He also went by the nickname “Mr. Hannack,” no doubt on account of Olomouc being the center of the ethnic Hannakia region of central Moravia. He worked in Purcell’s London from ca. 1687 for over a decade, and wrote a now-lost ode on the death of Purcell, “Weep, all ye muses.” He later relocated to Germany and finished his career in Mannheim. His music combines Purcellian elements with Moravian folk strains.

Finger’s Sinfonia in F comes from manuscript partbooks belonging to the collection of the Dresden Hofkapelle, where somebody had been collecting his music. He cast it in the style of such Neapolitan contemporaries as Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725). The style demands a high level of interconnectedness between different sections of the ensemble in order to create melodic continuity: a tune begun in one part of the orchestra will pass seamlessly like the baton in a relay to continue in another. The names of Dresden musicians on the surviving partbooks provide evidence of its performance sometime between 1709–1728, when concertmaster Jean-Baptiste Volumier (1667–1728) led the band.

Next to Vivaldi, Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679–1745) will be the other familiar name to Tempesta audiences from our past concerts. Zelenka hailed from the Czech market town of Louňovice pod Blaníkem, about 30 miles southeast of Prague. Like other Bohemians, he left his home country in order to make a living as a musician. From 1710 until the end of his life he worked at the Dresden Hofkapelle, the most prestigious musical post in Europe. He was engaged first as a bass player, but soon after also as a composer.

Zelenka jotted in Italian, “Concertos 6 made in a hurry in Prague 1723,” onto the autograph of his Concerto a 8 Concertanti, suggesting that this is one of six that he produced while back home. Zelenka is one of the most surprising composers of the high baroque. He constructs this concerto’s outer movements around classically chiseled ritornello themes, but adds melodic angularity, metrical asymmetries, and non-traditional harmonic twists that surely come from music he heard as a boy in a Slavic land. Such writing invites the listener to open his ears to more exotic possibilities for beauty.

The origin of Philipp Jakob Rittler (1637–1690) is unclear, but he did attend a Jesuit secondary school in Opava, Czech Silesia, where he began composing. He entered the priesthood and spent his life as chaplain at the episcopal court at Kroměříž, Moravia, of Karl Liechtenstein-Castelcorno, Bishop of Olomouc, where he also directed music. Rittler is the exception among these Bohemian musicians in that he worked in Bohemia, albeit supported as clergy. As a side note, the Bishop’s Palace at Kroměříž is where some scenes for the movies Amadeus (1984) and Immortal Beloved (1994) were shot.

Rittler’s Thousand-Guilder Sonata is an all-strings piece, dominated by a pair of violins against three violas and bass. The “thousand guilder” moniker remains a mystery. The long-standing source for this sonata had been two sets of manuscript partbooks in the Uppsala University Library, confusingly credited in one set to Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (1623–1680), and in the other to Antonio Bertali (1605–1669). Most recently, however, musicologist Konrad Ruhland attributes the work to Rittler. Like the Capricornus sonata, this piece combines late Renaissance ideas about instrumental consort writing with early baroque innovations in writing idiomatically for instruments.

Stamitz. Wikimedia Commons.

The great early classical symphonist Jan Václav Antonín Stamic (1717–1757), better known by his Germanized name Johann Wenzel Anton Stamitz, was born in Německý Brod in Bohemia/Česky. He attended Jesuit secondary school in Jihlava and university in Prague. By 1741 he was in Mannheim, Germany, where he would remain.

Stamitz was critical to forwarding the development of the classical symphony, and his work as composer and as orchestral leader drew great attention to music at Mannheim. One of his achievements was the codification of the four-movement symphony to the sequence i) fast, ii) slow, iii) minuet, and iv) very fast. Other hallmarks of Stamitz’s “Mannheim” style include the notation of sustained, dramatic increases and decreases of volume. These features are on display in this Symphony in F, opus 4 number 1, a mature work composed between 1752 and 1754. Stamitz’s six opus 4 symphonies were

published posthumously in 1758 by Huberty in Paris.

Richard Stone & Gwyn Roberts

Simplified Czech pronunciation

| • Stress normally on first syllable, e.g. Zelenka (ZE-len-ka, i.e., not ze-LEN-ka). | |||

| • Voiced consonants l, r, n, m can behave as quasi-vowels: e.g., Brno (BRR-no). | |||

| • Accented á, é, í, ó, ú, ů ý = lengthened vowel: Janáček (YA-nā-tchek). | |||

| letter | rule | letter | rule |

| a | open a, like far | c | ts: Stamic (STA-mits) |

| e | open e, like yes | č | tch: Čistá (TCHI-stā) |

| ě | ye: e.g., hrabě (HRA-bye) | ch | kh like Bach: Vrchlabí (VR-khla-bī) |

| mě | mnye: e.g. město (MNYE-sto) | h | firm h: Jihlava (YI-hla-va) |

| eu | eu like pneumatic | j | y: Jan (yan) |

| i | open i, like it | ni | nyi: Kounice (KOW-nyi-tse) |

| o | closed o, like open | ň | ny: Louňovice (LOW-nyo-vi-tse) |

| ou | ow like know: Olomouc (O-lo-mowts) | ř | = rrzh: Křinec (KRRZHI-nyets) |

| u | closed u, like rule | š | sh: škola (SHKO-la) |

| y | closed i, like Betty | ž | zh like television: muž (muzh) |