People always love stories. The three hundred years between now and the baroque shrink to nothing when you consider how people love their books.

The seventeenth century saw the beginning of the modern book world. It launched the bestseller, commercial theater, opera, ballet, and multi-media extravaganzas. People—middle-class and rich people, anyhow—got together to argue and rave about hot new releases. They flocked to the theatre to see their favorite stories on stage.

And like today, books inspired art in other media. Each of the four works in Tempesta di Mare’s Great Books program is from a different place and a different era. But they all have something in common. Just like the billboards say, they let you “Experience the Story Like Never Before!”

Purcell: The Fairy Queen, 1692 / Shakespeare: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, c.1600

Theater erupted in London when stages reopened after having been closed for twenty long years by the Puritans. Theater-crazed Charles II, restored to the throne in 1660, ushered in a thirty-year Golden Age of the performing arts in London. Daring entrepreneurs launched new theaters that combined English tradition with the latest technology and effects from the continent (flying! disappearing! women on stage!) to create a new, distinctively-flavored and jaw-dropping entertainment.

On the heels of Purcell’s previous smash hits at the Dorset Garden Theater (Dioclesian and King Arthur), The Fairy Queen was an ultra-deluxe “semi-opera” revival of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. It provided Shakespeare’s spoken words but added singers, dancers, new songs, and lavish production numbers to astound and amaze in the finest Restoration style. In fact, The Fairy Queen was the “Restoration Spectacular” to end them all, with its twelve-foot fountains and live, dancing monkeys. It practically bankrupted the theater.

Fortunately, Purcell’s enchanting music endures long after the fountains have bubbled their last.

The seventeenth century saw the beginning of the modern book world. It launched the bestseller, commercial theater, opera, ballet, and multi-media extravaganzas. People—middle-class and rich people, anyhow—got together to argue and rave about hot new releases. They flocked to the theatre to see their favorite stories on stage.

Telemann: Burlesque de Quixotte, (18th c.) / Cervantes: Don Quixote, 1605

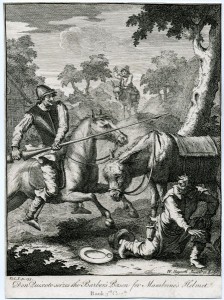

Don Quixote has been an international sensation since it first appeared in 1605 (part 1) and 1615 (part 2). It was translated into English in 1612, French in 1614, and Italian in 1622. The reading craze in general took longer to catch on in Germany than it did in other countries, but once it hit, it hit hard. Don Quixote got its first German translation in 1648, which was also the first illustrated version.

People all over Europe responded to Cervantes’ lovably delusional Don Quixote, who only thinks he’s a knight in shining armor, and his down-to-earth sidekick, Sancho Panza.

Cervantes’s humor must have appealed particularly to Telemann, whose own sense of humor peppers his work. In tribute to the comic Don, he wrote Burlesque de Quixotte, an orchestral suite (an overture followed by a set of character pieces) meant to stand alone as a performance piece, not incidental music for dance or drama.

Don Quixote gives Telemann a chance for fun, with a mock-pompous overture for the mock knight, and an oversentimental love theme for his imaginary ladyfriend. But the suite also provides real bravura writing as it describes the Don’s windmills as they whirl across the orchestra, as well as sweet rustic passages for Sancho Panza.

During his career, Telemann wrote over one hundred and twenty orchestral suites. The Burlesque de Quixotte appears to have been one of the most popular. And for good reason.

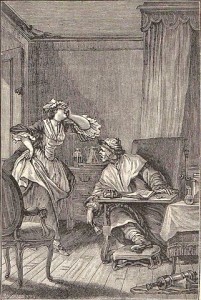

Charpentier / Molière, incidental music for Le Malade imaginaire, 1673

Molière’s “comedy-ballets,” Le Malade imagainaire and Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, were performed for Louis IV and his courtiers—some of whom also performed in the show as dancers. Molière’s plays are constantly performed today, but rarely with the songs, dance and music intended by the playwright. They also appeared in book form during his lifetime, in both authorized and pirated editions.

Lambasting the hypocrites and liars that surround us, his plays were controversial to say the least: he was charged with blasphemy for Tartuffe. As such, they must have been Topic A for discussion in those growing and increasingly influential hotbeds of French thought, the salons.

Semi-informal gatherings where people exchanged ideas and opinions, the salons were organized by remarkable women, the salonnières, all of them readers and many of them writers. Salonnière Madeleine de Scudéry, for instance, wrote Clélie: histoire romaine and Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus—both extremely popular and the latter, at 8,000 pages, one of the longest novels ever written.

Not only was Molière read in the salons, he gave readings there, too. His plays, sparkling gems in the difficult genre of comic writing, could hardly have been possible without the thoughtful feedback he received from members of his discerning and articulate audience. And they could dance, too.

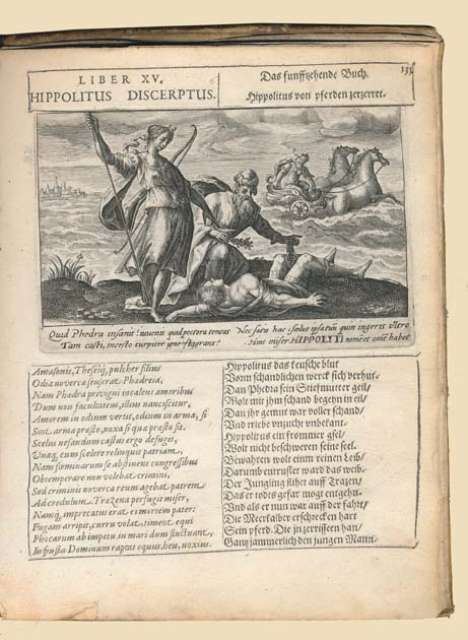

Rameau, ballet music for Pygmalion, 1748 / Ovid, Metamorphoses, 8 AD

Metamorphoses, the Roman poem that brought classical mythology to the modern world, has got to be one of the all-time bestsellers. Innumerable editions have gone to press since printing was invented. Metamorphoses was published in new translations into English, Dutch and French in 1723, making Ovid’s beautiful poetry even more accessible to people who could not read Latin, like as the avid new reading class of women.

At 65 years of age, Jean-Philippe Rameau was the alpha male of the Paris Opéra. By the time he wrote Pygmalion in 1748, a delicious one-act, multi-media confection of dance, song, and orchestra, he was so successful and popular that the Opéra limited him to only two new works a year, “for fear of discouraging other composers.” He is one of history’s late bloomers, though. He’d been a distinguished music theorist and keyboard performer for decades before he caught the theater bug and wrote his first opera at age 50.

For this production, he chose one of the really sunny poems from Ovid, where the sculptor falls in love with his creation, she reciprocates, the gods give their blessing, and the poetry is its most luscious:

[Pygmalion falling in love with his sculpture, 1717 English translation by Dryden, Garth et al:]

It caught the carver with his own deceit:

He knows ’tis madness, yet he must adore,

And still the more he knows it, loves the more:

The flesh, or what so seems, he touches oft,

Which feels so smooth, that he believes it soft.

In Paris, Rameau was writing for some of the best theater artists in the business. Paris Opéra company dancers, no longer the amateur courtiers of the Louis XIV era, were professional virtuosos capable of fully realizing the expressive potential and emotionalism of Rameau’s music. He gave them something to sink their teeth into when he wrote Pygmalion’s evocative scene of the statue changing from stone to flesh. And followed it up with a delightful interlude when the gods teach her how to move and—of course!—dance.

The music is as delectable as the poetry and the story has a happy ending. What could be better? Pygmalion became a big success and Rameau’s most-performed opera.