Holding the music in his hand was Richard Stone’s first unforgettable experience while preparing the upcoming Tempesta di Mare concert, Rescued by the Red Army: rediscovering Johann Gottlieb Janitsch. Stone, Tempesta di Mare Artistic Co-Director, visited Berlin last summer to work with the fabled, newly-rediscovered Berlin Sing-Akademie collection, preparing modern premieres of Janitsch’s work.

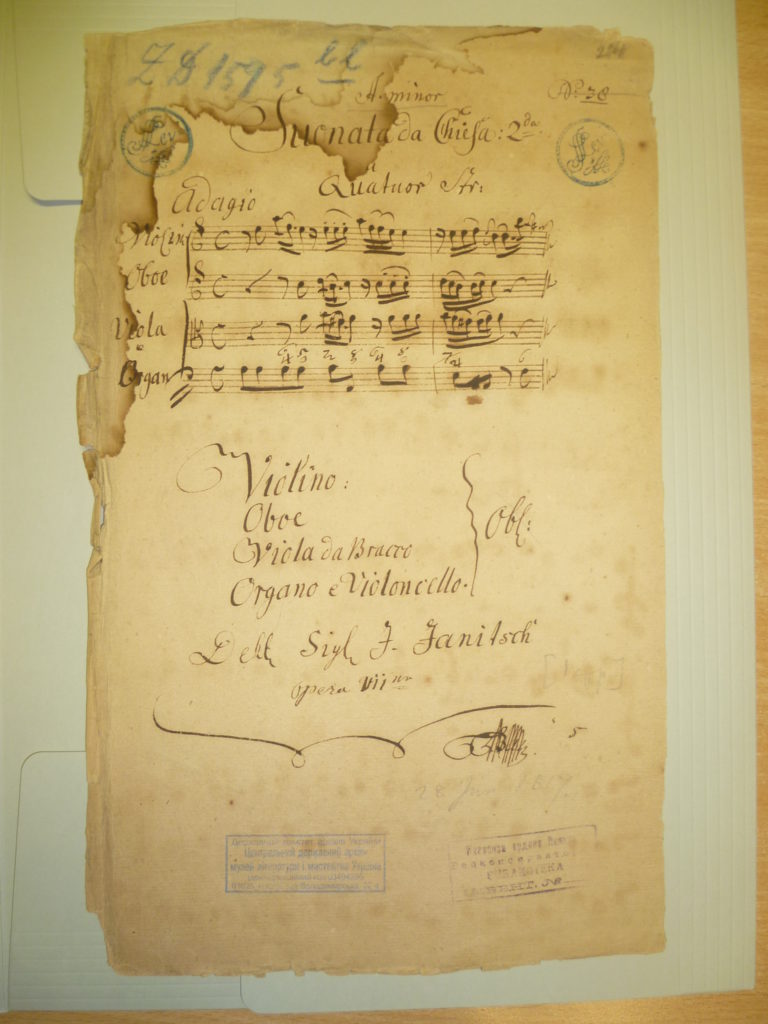

It was emotional, Stone says. The partbooks were still folded into their original eighteenth-century cover, labeled in the beautiful, copperplate handwriting of their original patron, Sara Levy. But they carry the scars of war right on their faces: when the music was seized by the Russians as war trophies in World War II, Soviet bureaucrats nonchalantly stamped over Levy’s titles twice, once for intake and once for outgo. “Purple was for in, blue was for out. The guys who were processing the music must have read only Cyrillic, so they’d just stamp anyplace. On a Beethoven manuscript, they stamped right on top of his signature,” he says. The Sing-Akademie music was seized by Soviet soldiers in Berlin in 1945 and hidden in Kiev until 1999.

It was emotional, Stone says. The partbooks were still folded into their original eighteenth-century cover, labeled in the beautiful, copperplate handwriting of their original patron, Sara Levy. But they carry the scars of war right on their faces: when the music was seized by the Russians as war trophies in World War II, Soviet bureaucrats nonchalantly stamped over Levy’s titles twice, once for intake and once for outgo. “Purple was for in, blue was for out. The guys who were processing the music must have read only Cyrillic, so they’d just stamp anyplace. On a Beethoven manuscript, they stamped right on top of his signature,” he says. The Sing-Akademie music was seized by Soviet soldiers in Berlin in 1945 and hidden in Kiev until 1999.

Once opened, the music had even more stories to tell Stone, stories about their earlier life in the music-mad, glittering salons of late 18th-century Berlin. “These were part books that musicians used in performance, and their markings remained in the music. I got to see all the articulations, slurring, tonguing and bowings marked in by the performers themselves.” As Stone worked, he began to realize his kinship with these long-dead virtuosi with whom he shares the intimacy of musical language.

And then Stone assisted the music in telling a new story. Entering the parts into his music engraving software, he was able to assemble them back into scores and play them in the library on the trusty speakers of his Macbook. “The librarians and researchers all gathered around to listen to this wonderful music as it was being performed again for the first time since the late 1700’s.”

Which brings up an essential paradox of the re-discovery of the Sing-Akademie collection: why was this great music by a master of the Berlin baroque so unknown and un-listened-to before being taken away by the Soviets and hidden for fifty years? Why did it take two centuries and an army to find an audience?

“The quick answer,” says Stone, “is that it was a private collection, not open to the general public. But the deeper answer is that until recently, people would have been indifferent to much of the music. It suffered from not being Bach.”

The collection once contained a lot of J.S. Bach. In fact, Felix Mendelssohn adapted the collection’s St. Matthew Passion score for his famous 1829 Sing-Akademie revival of the work. But the J.S. Bach contents were sold in the 1850’s. Without that, the collection excited less interest. Even though it still held Haydn, Handel and Mozart material and that Beethoven manuscript, its concentration in other German composers failed to grip nineteenth-century imagination, and research ceased. Even Telemann, lavishly represented, was undervalued even through the 1930’s, along with other composers suffering from Not-Bach Syndrome: Biber, Buxtehude and Froberger, Janitsch, Graun, and Hasse, even the Bach sons W.F. Bach and C.P.E. Bach.

But times change, often for the better. There’s a new, What-Else-Is-Out-There-Besides-Bach generation now. In fact, scholars were looking for C.P.E. rather than J.S. Bach in the 1990’s when they broke open the secret of the Sing-Akademie’s hiding place in Ukraine. Richard Stone feels that a collection of fabulous lesser-knowns like this has entered public access at just the right time to receive the attention it’s due.

“There’s a real spirit of discovery out there. People know enough now to figure out that even Bach was capable of producing some big fat snores that go on for too long. Even Mozart has his dogs. People are sophisticated enough to go beyond brand names, to seek out what’s good, what’s exciting, what defines quality in this music. They’re open to something new.”

Which is why, offered access to the collection, he and Artistic Co-Director Gwyn Roberts chose to concentrate on the admittedly obscure Janitsch. “We’ve been looking for a chance to play Janitsch because his music—well, the few works by him that have been known up to now—is gorgeous. We played his Quartet in G, Op. 1, for recorder, oboe, violin and continuo early in Tempesta’s history, and it’s always been a big favorite of ours. When we learned that we might have access to the Sing-Akademie collection, we knew right away this was our chance to really do Janitsch.”