by Anne Schuster Hunter

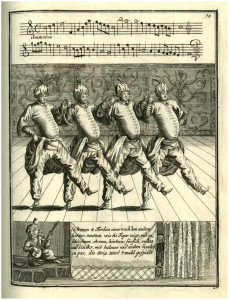

Gregorio Lambranzi, Nuova e curiosa scuola de’balli theatrali/Neue und Curieuse Theatrialische Tantz-Schul (Nurnberg: Joh. Jacon Wolrab, 1716), part II, plate 38. UCLA, Charles E. Young Research Library, Library Special Collections

To Europeans in the early 1700’s, the continent was getting smaller and the world was getting bigger. People in cities like London, Hamburg, and Dresden were increasingly aware of what lay beyond their city walls. The bubble of European parochial isolation didn’t exactly burst at the turn of the 18th century. But it started to tear.

These were global cities. Businesses like the Dutch and English East India Companies had became huge and powerful. Traders sent back reports and booty from their encounters overseas, soldiers battled on the European borders and came back with stories and oddities to share at home.

European feelings about their formidable adversaries in war and profitable trading partners in peace elsewhere in Europe, in the Balkans, the Middle East, Asia and the Americas were clearly complex, but general curiosity into differentness was undeniable. Curiosity extended among cultured people to the different customs of people in other parts of Europe and to the “different” folk living among them, tending the streets, villages, fields and forests.

The bubble of European parochial isolation didn’t exactly burst at the turn of the 18th century. But it started to tear.

In the upcoming concert The Nations, Tempesta di Mare salutes baroque composers who discovered rich musical territories in the new globalism. They include Jan Dismas Zelenka, Czech-born, who refused to give up his native Slavic sound even in the ultra-refined musical atmosphere of Dresden. Johann Helmich Roman introduced the Italian style of music to the remote Swedish court. Bucking fads, Matthew Locke brought the old English sounds of consort music back to the baroque London stage in The Tempest, “Rustic Air” and all.

In the program’s set-piece, his “Folk Suite,” Georg Philipp Telemann uses the fashionable “tour of nationalities” to blow open the color potentials of the baroque orchestra. With nimble mimicry of tolling bells and tapping feet, it’s easy to see how concert suites like this made Telemann the most sought-after composer of the era. He was a well-known admirer of eastern folk music and here offers a fresh and distinctive take on Turkish rhythms and harmonies.

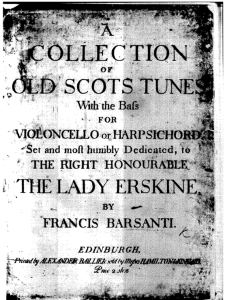

And then there’s Francesco Barsanti. An Italian—Tuscan—Barsanti emigrated to England but then made his way to Scotland, at that time considered the least-tamed and most exotic part of the British Isles. By all musical evidence, Barsanti completely fell for the romance of the northern wilds. Scholars consider his collection of thirty Old Scots Tunes to be the most attuned and sensitive to the nuances of highland music of the period. His concert music such as the Overture in D on the Nations program echoes the folk culture he adopted.

And then there’s Francesco Barsanti. An Italian—Tuscan—Barsanti emigrated to England but then made his way to Scotland, at that time considered the least-tamed and most exotic part of the British Isles. By all musical evidence, Barsanti completely fell for the romance of the northern wilds. Scholars consider his collection of thirty Old Scots Tunes to be the most attuned and sensitive to the nuances of highland music of the period. His concert music such as the Overture in D on the Nations program echoes the folk culture he adopted.

Barsanti is one of the many composers who disappeared from history when Baroque music went out of fashion in the 19th-century, but now, with advocates like Tempesta, is undergoing reappraisal and a terrific second act. Welcome back to a new and newly appreciative century, Signor Barsanti! It’s a small world, after all.