Medieval cartographers used to draw dragons and sea monsters into the as-yet unknown regions of their maps. It’s the origin of “here be dragons” (hic sunt dracones). Those are the places where we like to go treasure hunting.

The exploration and discovery hasn’t always been about pieces of music, per se. At times it’s been about discovering and developing a more specific approach to a particular historical or national style. For example, we spent two years as a group refining our approach to French music from the time of Louis XIII to that of Louis XV, immersing ourselves in the heady music of Lambert, Lully, Charpentier, Marais, Rebel, Leclair, and Rameau, and those are just the ones whose music we recorded in 2015 and 2016.

Throughout last season, we took extra rehearsal time as a group to delve into late Renaissance consort style, something most of us don’t learn in music school. Most baroque music is not written in consort style. But it is the style of music that Handel’s and Bach’s teachers grew up playing, for instance, and which became part of the musical DNA that their teachers imparted to them. This in turn played into those later baroque composers’ expectations of delivery, balance, and so on in their music. Having taken this step backwards, we could play baroque music looking forward from the perspective of the preceding style. It changed things for us noticeably.

The other sort of expeditions we’ve taken have been immersions to learn what’s distinctive about one composer’s voice as opposed to that of contemporaries writing in the same style, and to bring that knowledge to our interpretations. We did that with Fasch and Janitsch and are about to do it with Telemann—one of our heroes—next season. Sensitized to what’s special about Fasch, for instance, we can bring a specificity and dimensionality to his music that wouldn’t be there if we played him as though he were Handel, or worse yet, in some abstractly generic “high baroque” style.

This program showcases four pieces that represent discoveries for us—of music, style and voice—alongside one of the most beloved pieces in the world: “Spring” from Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. And, by the way, happy 15th birthday, Tempesta di Mare!

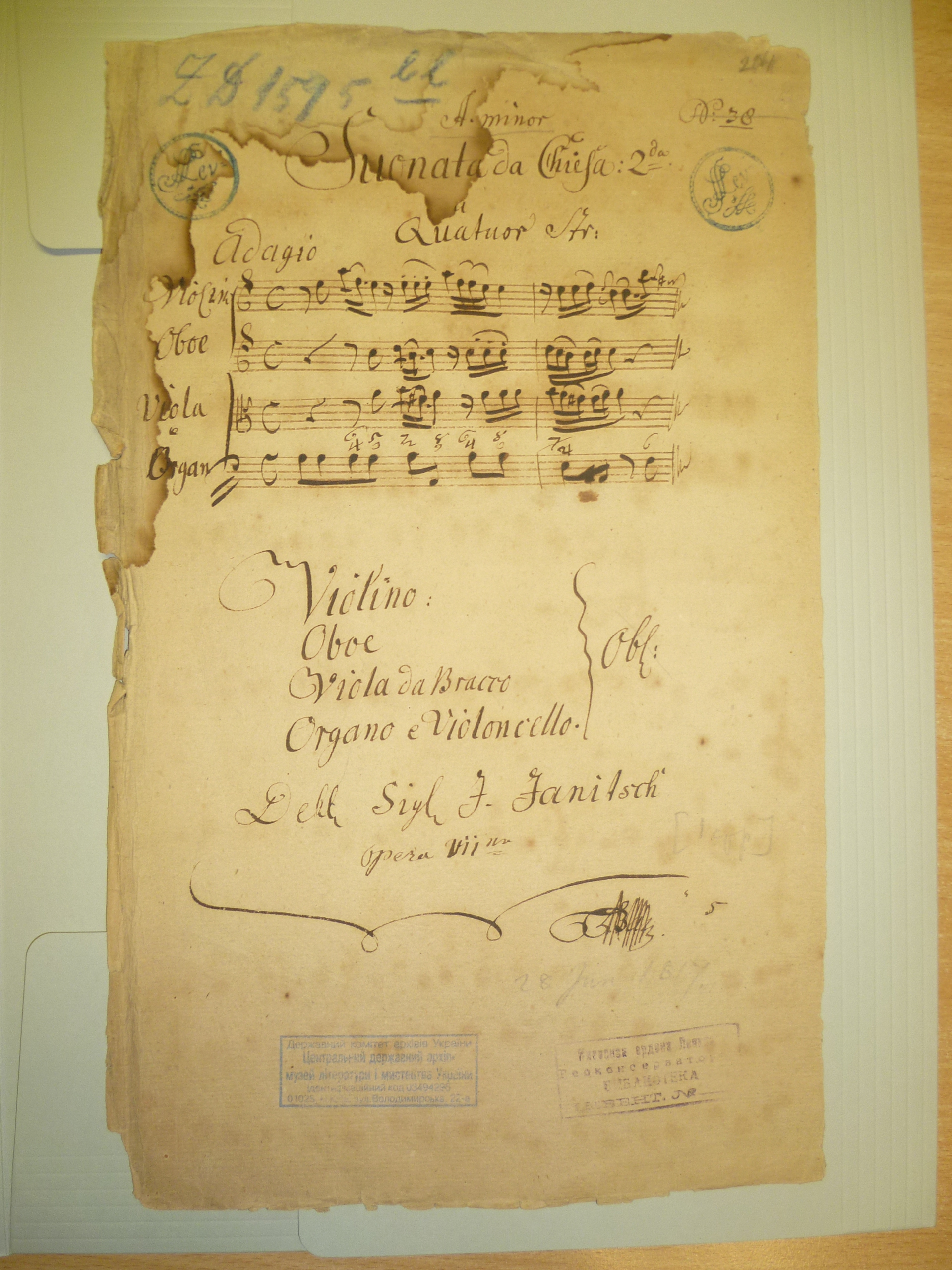

Johann Gottlieb Janitsch was one of the more distinctive exponents of the late-baroque “Berlin School,” which also included C.P.E. Bach, W.F. Bach and J.J. Quantz. In 2009 we were in Berlin researching chamber music by Janitsch in a recently repatriated collection that the Red Army had taken to the Soviet Union as war treasure and stashed in Kiev. It was then that we stumbled across his Ouverture Grosso in G for Double Orchestra. We transcribed it from manuscript and gave its modern premiere on our Philadelphia series in May 2011. It is one of only a handful of orchestral works by Janitsch to survive.

The manuscript from which we copied this piece belonged to Daniel Itzig, finance minister to Janitsch’s employer Frederick the Great and father of the Itzig sisters who are the subject of our January production, Sara and Her Sisters. Formally, the work has the high-baroque trappings of an earlier generation. The bipartite ouverture movement with its old-fashioned, churchy fugue, the closing bourée, and the dense counterpoint throughout all smack of old-school. Yet Janitsch treats the intermingling melodies and resultant harmonies of the two ensembles in the most current style, resulting in a buoyant, chatty work with an Enlightenment sensibility.

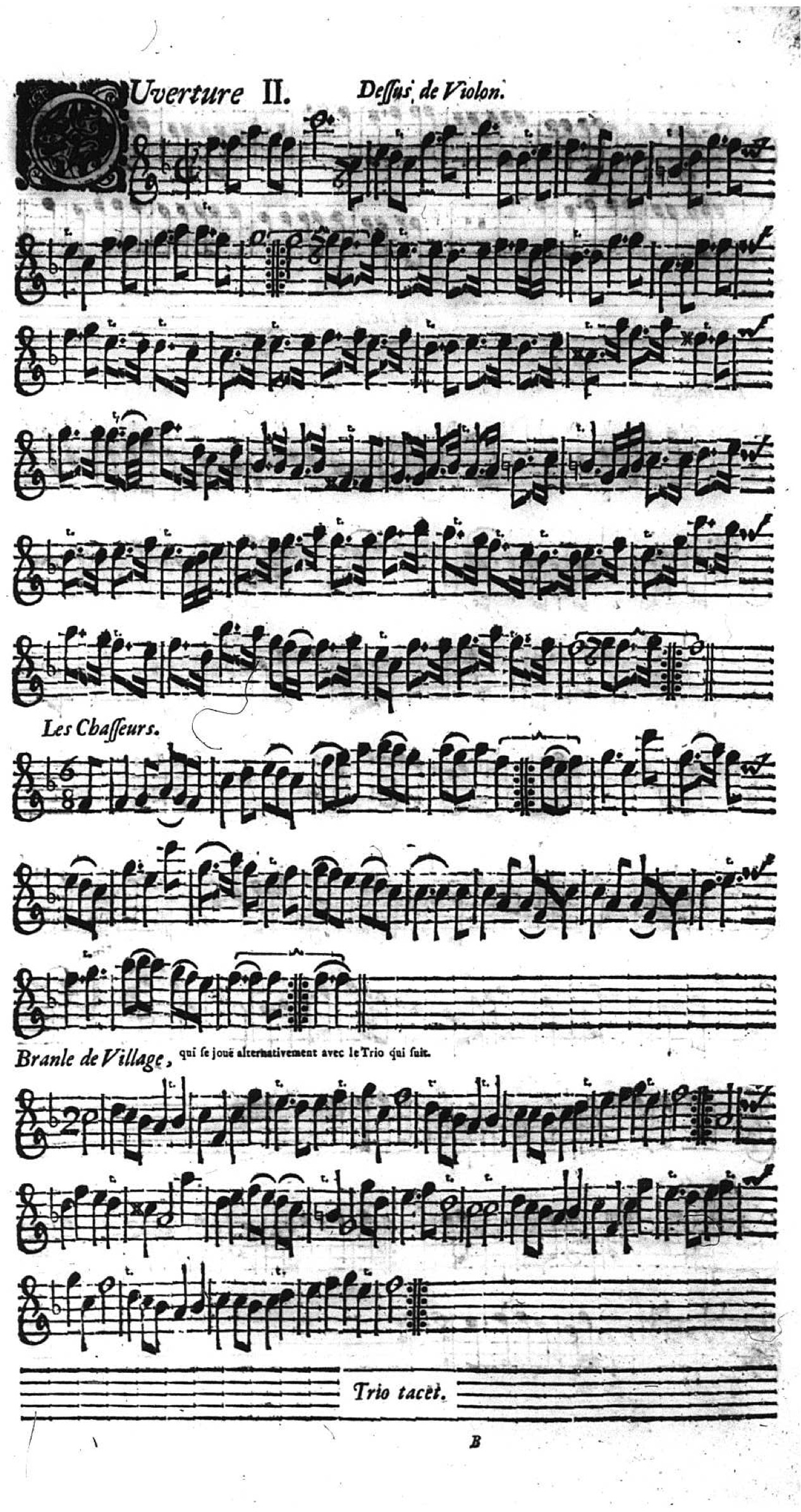

We first performed music by Johann Sigismund Kusser in March 2012, on a program introducing a whole raft of new-to-us composers. The suite that we premiered in that concert became an instant favorite, leading us to play another in March 2014.

Kusser’s family fled their native Hungary as religious refugees when he was a teenager, settling in Germany. His musical inspiration was the legendary French composer, music director and taste-maker Jean-Baptiste Lully, with whom he may or may not have studied in Paris, depending on whether you believe one contemporary account, which says that he did, or Kusser’s preface to one of his publications, which says that he taught himself Lully’s style.

Regardless of how he came by the knowledge, he spread it far and wide in Germany, England and Ireland. His volatile temper made it impossible for him to keep a job for very long, but his skill as a violinist, opera director, orchestra leader and composer would inspire each new employer until a quarrel led to his departure for another post.

Tonight’s offering, the Ouverture 2 in F, features more of the playfulness and rustic touches that make his work so attractive. Apollon Enjoué (Apollo at Play) was one of three collections Kusser published in 1700 under a gallicized version of his name, Jean-Sigismond Cousser. In the collection’s subtitle, he refers to these as “Theater Overtures with Several Airs,” making the opera inspiration behind this music clear to his public.

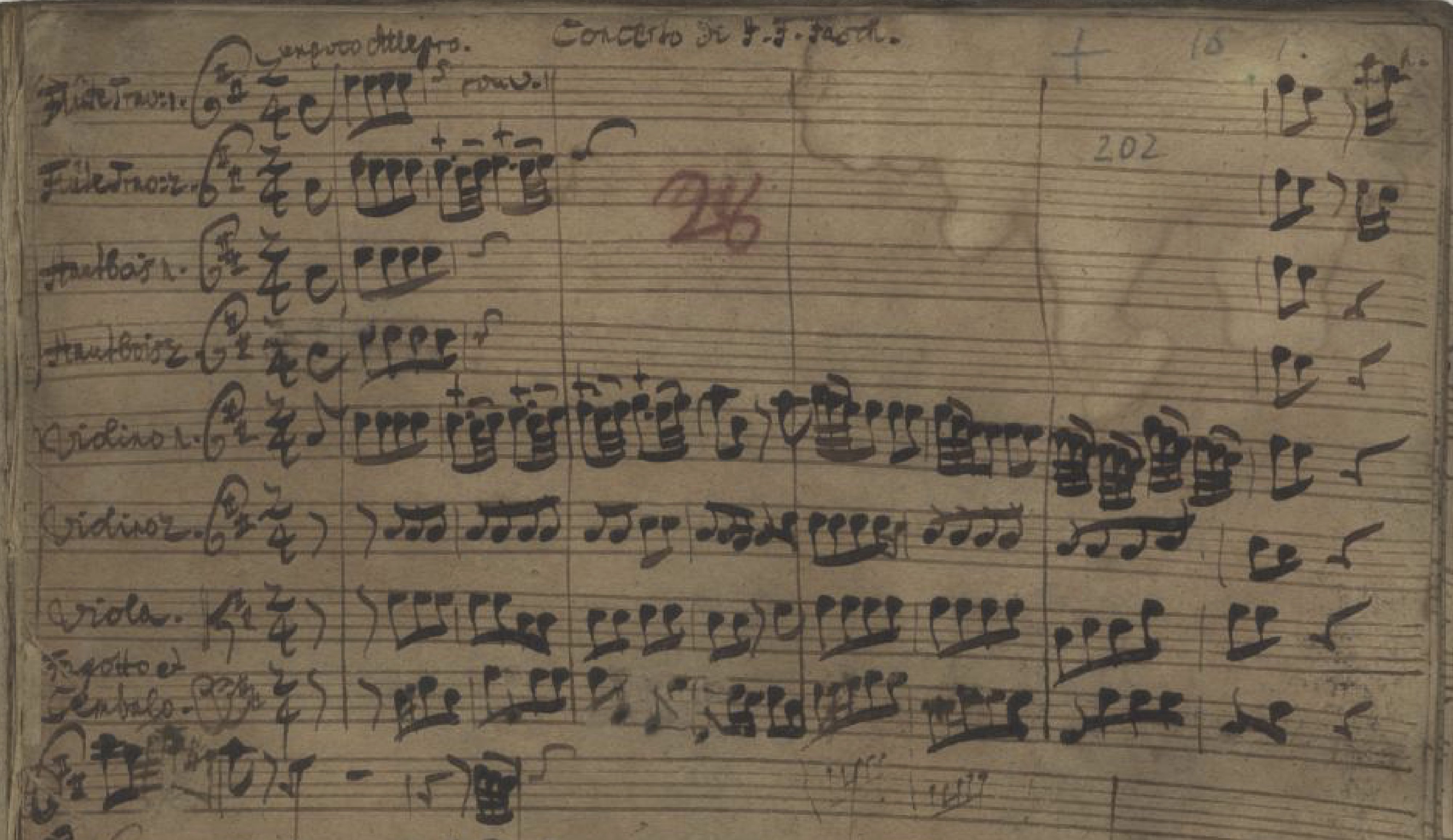

The music of Johann Friedrich Fasch has been one of Tempesta’s largest, deepest and most favorite projects. Since our Philadelphia Series began in 2002, we have performed 21 of his orchestral and chamber works, including 6 on tour in Germany at the International Fasch Festival, and recorded 14 of them for release on our 3 Fasch CDs, including 11 modern premieres. And that’s just scratching the surface: Richard Stone, Tempesta’s resident music software whiz, has more than 40 of Fasch’s compositions transcribed and ready to go, including many that haven’t been heard since they were new.

We first encountered Fasch through the chamber music that he wrote for his home court of Zerbst, some of which has been circulating in modern editions for decades. But it wasn’t until 2006, when we were in conversation with Brian Clark, musicologist and proprietor of the Scottish publishing house Prima la musica!, that we found out about the trove of his orchestral music that was emerging from the vaults in the Dresden library. Those manuscripts, water-damaged and long thought to have been lost in the firebombing of World War II, reveal Fasch as a major composer with an unmistakable voice, and have led to a worldwide, modern revival of his music with Tempesta at the forefront. You can read more about our work with Fasch on a dedicated page of our website: tempestadimare.org/fasch.

Fasch’s Concerto in D, FWV L:D22 is one of those works that emerged from the flooded vaults in Dresden. We perform it for the first time in the US tonight. Fasch’s personal twist on the German “mixed-taste” idiom includes long strings of bouncy and swooping figures in the fast movements, and lyrical, expansive lines in the central andante. Because he was writing for the famously fabulous Dresden orchestra, he also got to show off his great imagination as an orchestrator, deploying the flutes, oboes and bassoon in many combinations, with or without strings and continuo. This concerto is one of three by him for the same ensemble in the Dresden collection. The three concerti’s strong resemblance of style, scope and character suggest that they may constitute a set. We recorded the other two, the concerto in B flat, FWV L:B3 (2008) and the concerto in G, FWV L:G13 (2011).

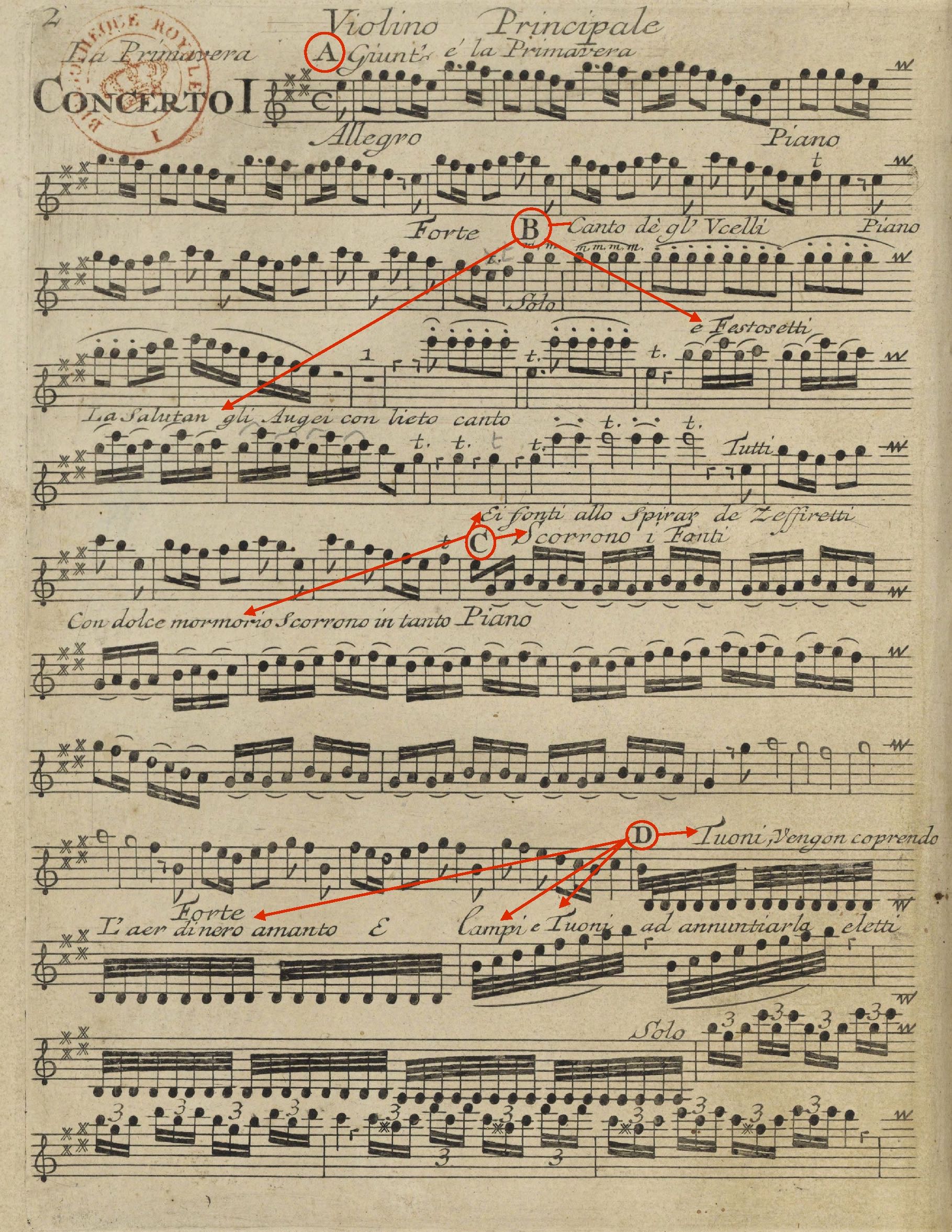

If Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons numbers among the most famous sets of classical music—not just baroque music—ever written, its opening concerto, Spring, is hands-down the most iconic member of the cycle.

Each of the four violin concertos that comprise The Four Seasons includes an illustrative sonnet on the subject of its time of year. Vivaldi published the sonnets inline with the music through all the part books, with each line appearing at the stage in the music that illustrates it. The sonnet appears below in these program notes. Each letter in the left column is where Vivaldi indicated the corresponding line of poetry in the music.

As much as these are descriptions tell the listener what Vivaldi is depicting, they also serve as guidance for the performers’ delivery. For instance, the line “La salutan gl’augei con lieto canto” (birds greet [spring] in happy song) corresponds to the first solo of the concerto—in fact a trio of solo violins—imitating a riot of birdsong, requiring at once a delicacy, virtuosity, and a cultivated disregard for an overly precise approach,* as would be appropriate for birds competing to attract mates in the spring. Likewise, the imitation of rustic bagpipes that opens the 3rd movement needn’t sound overly refined.

Our musicians will introduce and demonstrate these elements from the stage prior to the performance of the concerto so that you can follow along. Also, see our overview remarks on Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons on page 4 of the program booklet.

Illustrative Sonnet on the Concerto Titled “Spring”

While Jean-Philippe Rameau is far from an obscure composer, his orchestral music is rarely programmed and performed in this country—a situation we sought to address with our recent concentration on French Baroque music. Building on our experience with Fasch, which brought us to a deep and specific understanding of his style, we performed 25 pieces of French music in the course of two seasons and released two CDs of French orchestral music for the theater. With that project now under our belt, we’re excited to revisit this suite, which we previously performed in May of 2013, prior to our deep dive into French style.

Rameau’s 40-minute long acte de ballet, Pygmalion, debuted at the Paris Opéra in 1748. Based on a tale from Ovid’s Metamorphosis, it tells the story of the sculptor Pygmalion, who falls hopelessly in love with one of his statues and seeks the help of Venus. Cupid makes the necessary arrangements, and the statue comes to life, professing her love for the sculptor. The story of the newly living statue’s ensuing education also provided the basis for the Broadway classic, My Fair Lady.

Rapidly pinging repeated notes in the fast section of Pygmalion’s ouverture may be intended to depict the sound of the sculptor’s hammer. A little later, the pretense of needing to teach the statue to move provides a good excuse for French baroque opera’s obligatory ballet, in which Cupid and the Graces teach her the characteristics of each of the dance forms. This scene, which begins with the Air, très lent and concludes with the Tambourin, fort et vîte, is titled “the different characters of the dance” and presents just a short taste of each dance. Rameau’s quirky and specific approach to melodic filigree is on display throughout this suite, as is his gift for colorful orchestration.

__________________________

* Italian art had a name for a cultivated disregard, sprezzatura, making something look natural, effortless, not overly studied, and therefore allowing a certain amount of calculated imprecision to creep in to create this appearance. As in all theater, the disregard is pure illusion.