by Anne Schuster Hunter

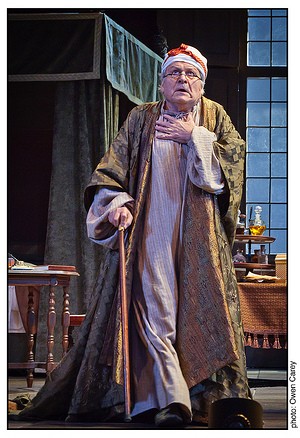

Argan (David Marguiles) in The Imaginary Invalid (Le Malade imaginaire) by Molière in an adaptation by Constance Congdon, directed by Chris Coleman at the Portland Center Stage Main Stage, 2011. www.pcs.org/invalid

Show business! Seventeenth-century show business, that is. The seventeenth century from mid-century on was theater boom time. Theaters sprang up everywhere all over Europe: private, semi-private, public, in palaces, in clubs, in salons, in big new commercial theaters, in pleasure gardens. And during the seventeenth century, a show always included music. This was the Golden Age of theater and the Golden Age was wired for sound.

In Purcell, Charpentier and ¡Zarzuela!, Tempesta di Mare plays theater music from seventeenth-century England, France and Spain (with a little Italian too), a long-forgotten repository of musical riches. It’s great stuff and fun to listen to. As it turns out, the old masters knew how to put on an even better show than we thought.

Part of Tempesta’s program showcases orchestral music that tagged on to the wildly popular theater phenomenon. Providing a nice full evening at the theater, producers added stand-alone musical selections like concerti by Corelli, Scarlatti, and William Babell to the featured event. Composers and publishers adapted theater music into orchestral suites and made them available for concert performance and home entertainment, too. The line between theater and orchestra hall was mighty fuzzy.

during the seventeenth century, a show always included music. This was the Golden Age of theater and the Golden Age was wired for sound.

Mr. Palmer as Careless and Mrs. Gardiner as Lady Plyant in The Double Dealer by William Congreve (acte IV scene 2), scanned from New English Theatre, 1777 edition, vol. 9. (Wikimedia Commons)

You can see playwrights leaning on music as a storytelling tool, heightening character and mood as well as driving plot. In Le Malade imaginaire, Charpentier’s music draws colorful character studies in big set-piece dance numbers. And throughout the play, it provides a classy foil to Molière’s rapid-fire verbiage, physical comedy, and earthy humor.

Congreve’s plays, like much English restoration comedy, are noted for their cool, cynical dissection of social mores. But in The Double Dealer, Purcell’s music adds heart, sweetening Congreve’s witty, brittle dialogue (“Tho’ marriage makes man and wife one flesh, it leaves ‘em still two fools”) with stately, melancholy airs and dances.

The Double Dealer and Le Malade imaginaire are classics, frequently revived today (particularly the Molière). But when baroque music fell out of fashion centuries ago, Charpentier and Purcell’s music stopped being used. These days, the Congreve is mounted more-or-less without music. Theaters find a lot of creative solutions for the Moliere, mixing up newly-composed music, aural soundscapes, pop songs and so forth.

If you don’t know what’s missing, you don’t feel the loss. Nobody’s saying that productions of old plays have to be historically informed. But by bringing this music back to life for us in concert form, Tempesta and their colleagues allow a fuller appreciation of an art that was always meant to be more than the sum of its parts. Bravo to that.

While playing some thumpin’ good tunes. Encore!