By Anne Schuster Hunter

When Tempesta di Mare presents not one, not two, but three Winters from three different Four Seasons in the upcoming program, Winter: A Cozy Noel, they’re not just inviting us to come and join the cheer by the glowing hearth.

That’s part of it, of course. To hear Vivaldi’s famous Winter paired with lesser-known but estimable Winters by Giovanni Antonio Guido and Christopher Simpson is a holiday treat for us long-time Four Seasons fans. It’s a real gift to be able revisit an old favorite and discover new ones in the process.

But Winter also delves into the heart of Tempesta’s year-long Four Seasons project, asking the question: why the Four Seasons? What drew Vivaldi to this subject, and Guido, and Simpson, and so many more? Seasonal change is nice, particularly if you live someplace with snow, but why is it getting the full-press treatment in Venice in 1723 (not so snowy)? Or Paris in 1717 (Guido), or London in the 1660’s (Simpson)?

But Winter also delves into the heart of Tempesta’s year-long Four Seasons project, asking the question: why the Four Seasons? What drew Vivaldi to this subject, and Guido, and Simpson, and so many more? Seasonal change is nice, particularly if you live someplace with snow, but why is it getting the full-press treatment in Venice in 1723 (not so snowy)? Or Paris in 1717 (Guido), or London in the 1660’s (Simpson)?

And other places too numerous to count. The Four Seasons was everywhere in the 17th and 18th centuries. The baroque didn’t invent it, of course. It’s an ancient theme—as old as weather and the Romans—but the baroque seems to have taken it to heart.

With all these new truths abounding—exciting and a little upsetting—is it any wonder that artists and musicians looked to the old allegories for aid in processing?

Yes, the Four Seasons was a very big deal. But then, from 1600 to 1750, the eve of the Enlightenment, nature itself was a big deal. New and amazing facts were emerging every day about flora, fauna, the microscopic world, geological formations, weather, stars, the universe, the self. Truths were morphing. Marvels were given physical causes. Religious skepticism burgeoned. Philosophy and literature were changing, and so were the arts.

Yes, the Four Seasons was a very big deal. But then, from 1600 to 1750, the eve of the Enlightenment, nature itself was a big deal. New and amazing facts were emerging every day about flora, fauna, the microscopic world, geological formations, weather, stars, the universe, the self. Truths were morphing. Marvels were given physical causes. Religious skepticism burgeoned. Philosophy and literature were changing, and so were the arts.

With all these new truths abounding—exciting and a little upsetting—is it any wonder that artists and musicians looked to the old allegories for aid in processing? Imagine hearing Vivaldi’s Winter with fresh, early 18th-century ears. It must have sounded raw, unmediated, noisy, crazy and Italian (which is, in fact, how people described Vivaldi’s performances). Which Vivaldi rationalizes in the sonnet accompanying the concerto: “…This is winter, which nonetheless brings its own delights.” Don’t worry, it’s not noise. It’s Winter.

Sometimes it takes allegory to tell the truth. Venetian Rosalba Carriera decided late in life to draw herself realistically—an uncharacteristic move for an otherwise conventional artist. She didn’t flinch, though. She showed what she saw in the mirror. It’s an amazing portrait—which she called Winter.

Sometimes it takes allegory to tell the truth. Venetian Rosalba Carriera decided late in life to draw herself realistically—an uncharacteristic move for an otherwise conventional artist. She didn’t flinch, though. She showed what she saw in the mirror. It’s an amazing portrait—which she called Winter.

A metaphor for change and renewal is a nice thing to have around, particularly when you are creating at the edge of the envelope. No wonder composers like Vivaldi, Guido and Simpson chose the Four Seasons for some of their most ambitious creations.

As we grope our way in a new world where facts and truths can seem uncertain and troubling, it’s not just instructive to experience great works like these that came to existence during an unsettled time. It’s a comfort.

And that’s a cozy thought, indeed.

Images:

Jan van Goyen, Allegory of Winter (pendant to Summer), 1625, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum. Wikimedia Commons.

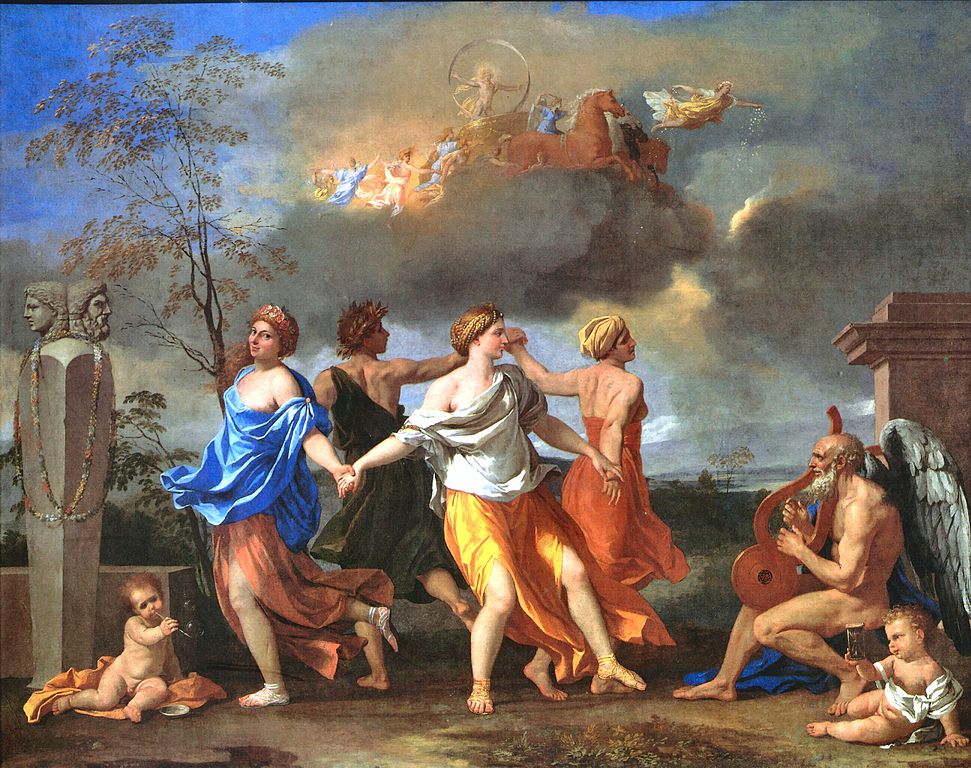

Nicolas Poussin, A Dance to the Music of Time (also known as Dance of the Seasons or Image of Human Life, 1634-’36, Wallace Collection, London. Wikimedia Commons.

Rosalba Carriera, Self-Portrait as Winter, 1730 or 31, pastel on paper, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Wikimedia Commons.

For further reading: Four Seasons fans should definitely look out for Michael Kammen’s A Time To Every Purpose, The Four Seasons in American Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2004). Kammen was a scholar of American cultural history, but this labor of love traces the motif from antiquity through the 20th-century.