by Anne Schuster Hunter

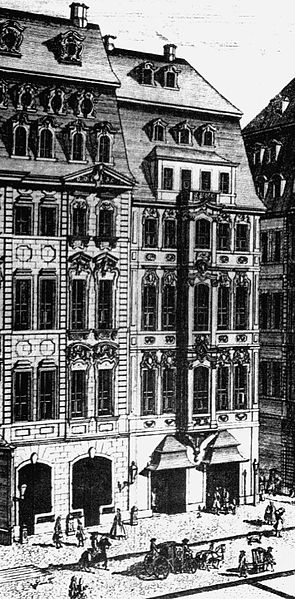

Zimmermann’s Coffeehouse in Leipzig, Germany. 18th century engraving by Georg Schreiber.

Bach’s career took an unexpected turn in 1729. He was 44 years old. His seven years since becoming Kapellmeister of Leipzig’s St. Thomas Church had been some of the most creative and productive known in the entire history of the world. So what do you do next, after you’ve written the Saint Matthew Passion, two great annual cycles of church cantatas and the B-minor mass? In Bach’s case, he seems to have given himself a real musician-style treat. He went down the street and put on some shows.

It’s the lesser-explored sunny, social side of Bach that Tempesta di Mare salutes in the upcoming Zimmermann’s Coffeehouse. And it gives the group a wonderful opportunity to play pieces to delight their fans from among the work that Bach himself used for the exact same purpose.

Zimmermann’s Coffeehouse gets its name from the Leipzig café in a swank, elegant neighborhood where Bach held free concerts weekly—and sometimes more frequently—from 1729 until more than a decade later. Scholars ponder over why in the world Bach chose to spend his valuable time like this. They point out the practical side of the Zimmermann gig, which gave Bach a chance to cultivate the local talent pool.

But maybe, just maybe, Bach also thought he was due for some fun.

But maybe, just maybe, Bach also thought he was due for some fun. From all evidence, Zimmermann’s sounds like it was an excellent room. What professional musician with talent to burn wouldn’t want spend a little time there every week, going out there and killing it?

Plenty of fun to be had in 1730’s Leipzig. Photo: Cover to Christian Friedrich Boethius’ songbook, Singende Muse an der Pleisse, 1736.

In any event, from that point on and, it seems, with Zimmermann’s in mind, Bach produced a vast variety of chamber works, sonatas, and some secular cantatas, too—including the comic Coffee Cantata, which must have been a particular favorite with the coffee-swillers at Zimmermann’s—that are among the liveliest and loveliest in his œuvre.

His audience was ready to be entertained. They had money and leisure time and were eager to spend both. 1800’s Leipzig was having an amazing boom. The old medieval trading post was now a thriving metropolis and marketing mecca. Gorgeous baroque mansions were rising on every side. Promenades, fountains, gardens and parks criss-crossed the city and banked the river. Nightlife flourished, even more so after the Leipzig city fathers sprang for ultra-modern oil-burning streetlights in 1701.

Very modern indeed, both ladies and gentlemen (“cavaliers” and “dames”) came to the concerts, which were held inside during winter evenings and outside in late summer afternoons.

Inside was cozy. Zimmermann’s Café boasted two rooms roughly the size and dimensions of a Philadelphia storefront restaurant, perfect for chamber works like the violin and recorder concertos on Tempesta’s program or a wonderful evening of song. And Bach wasn’t above putting on a stunt or two there, like cramming a concerto for four harpsichords into the little rooms, which he undoubtedly did at some point.

Because owner Gottfried Zimmermann didn’t charge and was making his money on beverage sales, audience members must have been warmly encouraged to dawdle, talk, be comfortable and run up a bill. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine a sort of cabaret atmosphere. And during the summer, outside in a garden with soft breezes in the sweet northern light, could there have been a dance or two to Mr. Bach’s sprightly minuets and gigues?

All in all, bringing back times when the coffee was strong and life was good, Tempesta di Mare’s Zimmermann’s Coffeehouse should be a thoroughly enjoyable night at the theater. In fact, it’s almost like Bach planned it that way.

Oh, wait. He did.